Submitted by Christina Rozeik on Fri, 18/09/2020 - 16:01

250 years ago, over one-fifth of Londoners had contracted syphilis by their 35th birthday, historians have calculated in a study that offers the first robust estimate of the amount of syphilis infection in London’s population in the later eighteenth century. The same study shows that Georgian Londoners were over twice as likely to be treated for the disease as people living in the much smaller city of Chester at the same time (c.1775), and about 25 times more likely than those living in parts of rural Cheshire and north-east Wales.

Following years of painstaking archival research and data analysis, historians Professor Simon Szreter from the University of Cambridge, and Professor Kevin Siena from Canada’s Trent University, have just published their disturbing findings in the journal Economic History Review. Their findings could help to transform our understanding of the capital’s population structure, sexual habits and wider culture as it became the world’s largest metropolis.

The researchers are confident that one-fifth represents a reliable minimum estimate, consistent with the rigorously conservative methodological assumptions they made at every stage. They also point out that a far greater number of Londoners would have contracted gonorrhea (or, indeed, chlamydia) than contracted syphilis in this period.

“The city had an astonishingly high incidence of STIs at that time”, Professor Szreter says. “It no longer seems unreasonable to suggest that a majority of those living in London while young adults in this period contracted an STI at some point in their lives. In an age before prophylaxis or effective treatments, here was a fast-growing city with a continuous influx of young adults, many struggling financially. Georgian London was extremely vulnerable to epidemic STI infection rates on this scale.”

To maximise the accuracy of their estimates, Szreter and Siena drew on large quantities of data from hospital admission registers and inspection reports, and other sources to make numerous conservative estimates including for bed occupancy rates and duration of hospital stays. Along the way, they excluded many patients to avoid counting the false positives that arise from syphilis’s notoriously tricky diagnosis.

After making careful adjustments, Szreter and Siena reached a final conservative estimate of 2,807 inpatients being treated for pox annually across all institutions c.1775. By dividing this figure by London’s population, falling within the catchment area of the hospitals and workhouses studied, they arrived at a crude annual rate of treatment per capita.

By then comparing this with existing data for Chester – and making further adjustments to account for demographic and social differences between the two cities – they converted London’s crude rate into a comparable cumulative probability rate. This suggested that while about 8% of Chester’s population had been infected by age 35, the figure for London was well over 20%.

“Syphilis and other STIs can have a very significant effect on morbidity and mortality, as well as fertility”, Szreter explains. “So infection rates represent a serious gap in our historical knowledge, with significant implications for health, for demography and therefore for economic history. We hope that our work will help to change this.”

“Understanding infection rates is also a crucial way to access one of the most private, and therefore historically hidden, of human activities, sexual practices and behaviours.”

Full story: https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/syphilis-georgian-london

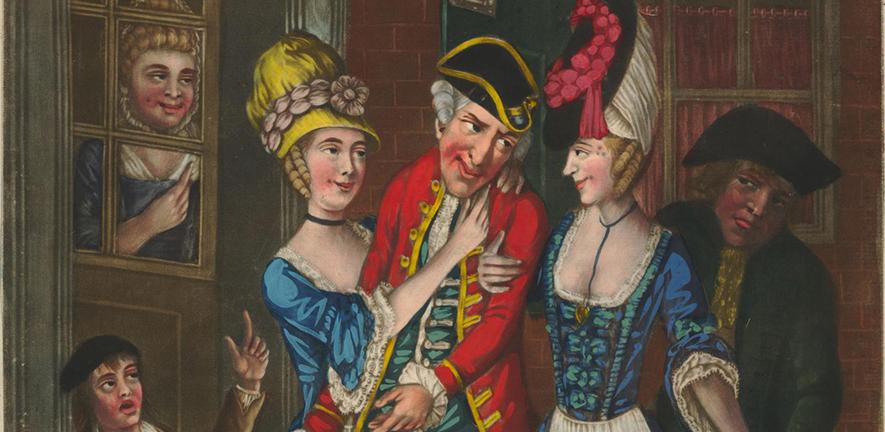

Image: An Evenings Invitation; with a Wink from the Bagnio (1773). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Reference

Simon Szreter and Kevin Siena, ‘The pox in Boswell’s London: an estimate of the extent of syphilis infection in the metropolis in the 1770s’, Economic History Review (July 2020). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13000.