Submitted by Christina Rozeik on Mon, 23/08/2021 - 10:08

Reproduction is all about cycles: menstrual cycles, treatment cycles, population cycles and more. A team of historians has analysed how metaphors of cycles and circulation have been deployed, and how they have linked reproduction to other major topics.

Cycles are among the oldest ways of grasping human existence, and of thinking about life and death, health and disease, as well as daily and seasonal rhythms of regeneration. From around 1800, life cycles and reproductive cycles became a focus of research and then a target of control.

Women’s monthly bleeding, long discussed as an ebb and flow, and increasingly pathologised as a periodic illness, was in the 1920s and 1930s reframed in terms of menstrual cycles. Menstruation was reinterpreted as the breakdown of the lining of the uterus, driven by hormonal changes in an ovarian follicle.

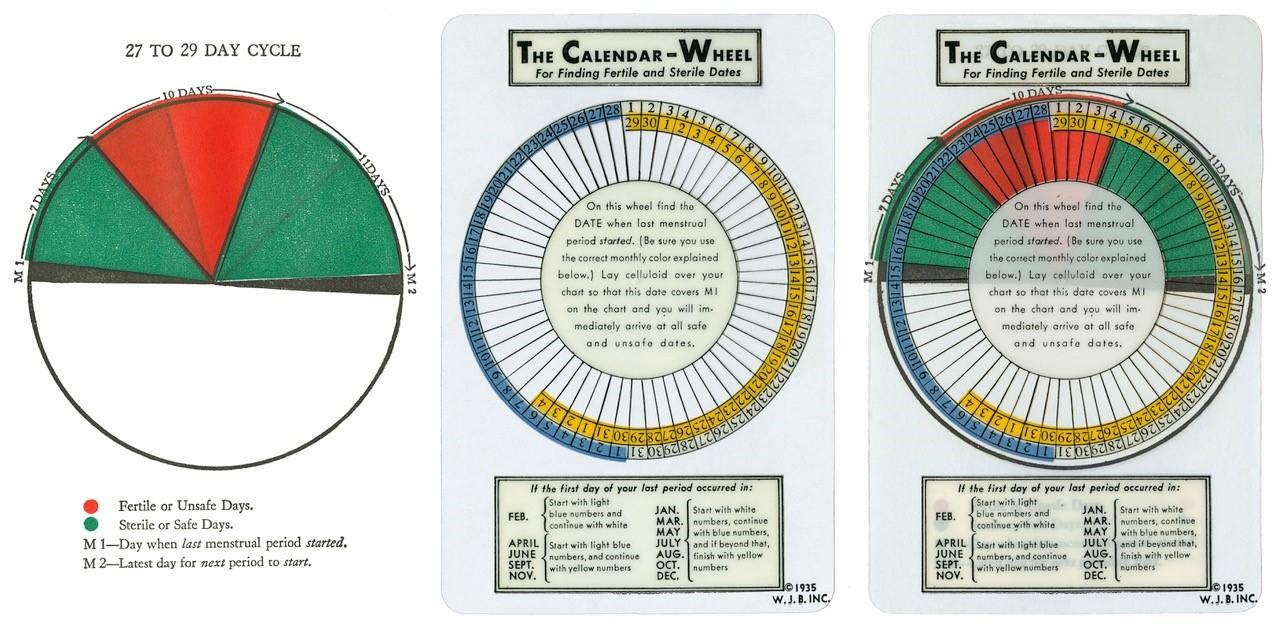

Some forms of contraception merely observed menstrual cycles. Women had annotated calendars for centuries, but the gynaecologists Hermann Knaus and Kyusaku Ogino promoted the rhythm method as a new practice of calendar marking. Other contraceptive methods intervened. From 1960, female sex hormones were marketed for birth control.

Infertility rose up the agenda in the 1970s, when in vitro fertilisation (IVF) turned menstrual cycles into treatment cycles. More generally, controlling life has involved selectively fostering as well as inhibiting cycles.

These are just some of the cycles that feature in a synthetic article published in the journal History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences. It is the work of an international team led by Nick Hopwood, who is in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science and a deputy chair of the SRI. SRI members Staffan Müller-Wille (HPS) and Lucy van de Wiel (Sociology) contributed, too.

Hopwood said: “It’s instructive to see how reproductive cycles interact with the other cycles that have shaped human societies and our relations with the natural world.” From the late eighteenth century, population levels were seen to depend on the capacity of land to grow food, and so as bound up with the circulation of matter. In the twentieth century, biogeochemical cycles, including of carbon and nitrogen, were tied to population cycles, not least through fears of environmental degradation. In Silent Spring (1962) the biologist Rachel Carson described how poisons were stopping the “wheel” from “turning” in nature’s “cycles of renewal”.

"Today," Hopwood added, "cycles are at the heart of assessing human impacts on Earth and of trying to mitigate them. Some commentators rehabilitate population control as a response to the climate crisis. But environmentalism also highlights the precariousness of reproduction in a polluted world.

“A broad, long-term perspective does not just show how these connections were made and how they have changed. It also alerts us to the powers of cyclic representations to make certain relationships and processes visible while obscuring others. That, above all, is what our article explores.”

The research originated in an Ischia Summer School on the History of the Life Sciences, which was funded by Wellcome, the National Science Foundation and History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences.

Image: Menstrual calendar-wheel. Chart, wheel and chart plus wheel from T. S. Welton, Rhythm Birth Control: The Modern Method of Birth Control (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1960).

Reference

Nick Hopwood, Staffan Müller-Wille, Janet Browne, Christiane Groeben, Shigehisa Kuriyama, Maaike van der Lugt, Guido Giglioni, Lynn K. Nyhart, Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Ariane Dröscher, Warwick Anderson, Peder Anker, Mathias Grote, Lucy van de Wiel and the Fifteenth Ischia Summer School on the History of the Life Sciences, ‘Cycles and circulation: A theme in the history of biology and medicine’, History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 43 (2021): article 89. DOI: 10.1007/s40656-021-00425-3.